Trusts have been around for centuries and are the common law equivalent to civil law foundations.

Trusts generally offer a very high level of protection against lawsuits, creditors, divorces, the government and plain bad luck. In addition, they are typically a key component of any succession plan.

A US trust setup works particularly well for non-US trust grantors. Traditionally, U.S. trusts used to be settled by non-US clients when they either owned U.S. property or had U.S. beneficiaries. But a US trust works best when its assets are held outside the U.S., and trusts established in popular trust jurisdictions such as Wyoming or Nevada present a viable alternative to offshore structures.

In what follows, we focus on the advantages a U.S. trust offers for “non-resident alien” trust grantors. We then take a closer look at why a Wyoming Asset Protection Trust offers advantages over more established trust jurisdictions, e.g. by allowing grantors to settle their trust anonymously and protect their assets without losing control. Finally, we propose a possible structure optimized for managing and investing crypto assets held in trust.

1. U.S. vs. offshore

The international political and regulatory climate has accelerated a clear “onshoring” trend, which is benefiting the United States for the following reasons:

- improved U.S. trust, tax, asset protection and privacy (not secrecy) laws;

- blacklisting of offshore jurisdictions as “fiscal paradises”;

- the U.S as arguably one of the deepest pool of legal expertise worldwide, based on precedent and centuries of case-law;

- forced heirship statute protection;

- the secrecy wall falling apart globally, with many offshore jurisdictions now forced into Ultimate Beneficial Ownership registers and disclosures;

- the Common Reporting Standard (“CRS”).

Three of the above reasons merit further elaboration:

First, many offshore (non-U.S.) trust and wealth protection jurisdictions are blacklisted by foreign countries via legislation or regulations. This blacklisting may result in negative treatment of offshore trusts and foundations. For instance, it is ever more difficult to get a bank account for an offshore entity. Singapore, which arguably was built on offshore wealth parked there, generally does no longer open bank accounts for offshore entities. Switzerland, traditionally the go-to place for a bank account for any type of entity, also became stricter: though it still caters to entities worldwide, Switzerland now automatically exchanges information with the home jurisdiction of entities’ Ultimate Beneficial Owners (see below).

Second, U.S. trust jurisdictions have statutes specifically excluding forced heirship claims. Such forced heirship may occur when the law of a foreign country do not recognize the concept of a trust and will in turn direct where assets will go at a person’s death.

Third, the Common Reporting Standard. CRS is most foreign jurisdictions’ version of the U.S. Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (“FATCA”) and is driven by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (“OECD”). In the same way banks outside of the U.S. have to report back to the I.R.S. when an American citizen uses financial services outside of the U.S. (or owns a corporate entity that does so), host country banks in most OECD jurisdictions automatically exchange financial account information to tax authorities of the jurisdictions in which customers are residents for tax purposes. Understandably, many foreigners are concerned with privacy under CRS and what type of information is automatically exchanged (see Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information in Tax Matters, OECD (2014). CRS was inspired by the financial reporting requirements established by FATCA and currently has more than 100 jurisdictions committed (see Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes,AEOI: Status of Commitments, OECD (November 2018). However, The U.S. is not a signatory to the Common Reporting Standard and hence does not automatically exchange financial account information to tax authorities of the jurisdictions in which customers who access financial services in the U.S. are resident for tax purposes. For instance, a German national can own an LLC in the U.S. and operate a bank account there without automatic exchange of account information by the U.S. to the German tax authorities.

The above goes a long way to understand why European families are increasingly choosing the U.S. over traditional locations such as Switzerland when setting up cross-generational wealth protection vehicles.

It also helps explain why the UBS office in Reno, Nevada is one of the fastest growing wealth management offices for UBS!

Who does UBS cater to out of the U.S.? Typically, international clients and not U.S. persons.

International estate planning follows some basic rules:

- U.S. persons are subject to U.S. income taxation on their worldwide income.

- Individuals who are U.S. persons are also subject to gift, estate and generation skipping transfer taxation on their worldwide assets.

- Non-U.S. persons are subject to U.S. income tax only on their U.S.-sourced income.

- Individuals who are non-U.S. persons are subject to estate, gift and generation skipping transfer tax only on U.S.-based assets.

Grantors

The above opens interesting possibilities for non-resident aliens (“NRAs”) as foreign grantors of U.S. trusts.

Relevant sections of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) provides that every trust is a foreign trust unless both of the following are true:

- A U.S. court can exercise primary supervision over the administration of the trust; and

- One or more U.S. persons have the power to control ALL substantial decisions of the trust.

Such “substantial decisions” mainly include decisions whether and when to distribute income or principal, how much is distributed, who can select beneficiaries, who can make investment decisions, who decides to terminate the trust, etc.

In Asset Protection Trusts, it is the grantor who retains these substantial decision-making powers. Consequently, a foreign grantor trust is a foreign trust for tax purposes, although it is governed by the law of the state in which it is formed and is administrated there.

Beneficiaries

For the purpose of this discussion, we also assume that the beneficiaries of such foreign grantor trust are not U.S. persons. U.S. persons include U.S. citizens, resident aliens (green card holders), and U.S. residents who meet the “substantial presence” test, generally those present in the United States for more than 183 days over a three-year period.

So a Foreign Grantor Trust (“FGT”) is a trust in which both the grantor(s) and its beneficiaries are not U.S. persons.

Such FGT is established as a “foreign” trust for U.S. tax purposes and is treated identically to an offshore trust, with the NRA treated as owner of the trust under U.S. tax laws.

Reducing or Eliminating U.S. Taxes

Even if they are considered foreign owners of a trust, a FGT could still become encroached in U.S. taxes if the Trust holds U.S. property or receives U.S. “source income”.

The rules are nuanced but there are three cardinal rules for NRAs who wish to minimize or eliminate U.S. taxes:

- Minimize contacts with the United States to avoid becoming U.S. residents for income or estate tax purposes.

- Minimize holding U.S. assets to avoid estate taxation. The solution here is to hold U.S. real estate, tangibles located in the U.S. and shares of stock of U.S. corporations through a non-U.S. entity (see below).

- Minimize taxable U.S. source income to avoid U.S. income taxation: all U.S. source income will still be payable by a non-U.S. entity, and thus subject to income tax withholding.

In Section 3, we will propose a structure that optimizes for the above in the context of crypto asset holdings. First, however we need take a closer look at the benefits of Wyoming as the jurisdiction for Foreign Grantor Trusts.

2. The Foreign Grantor Trust in Wyoming

As we have seen above, an FGT is established as a “foreign” trust for U.S. tax purposes and is treated identically to an offshore trust.

Then only nexus with the U.S. for FGTs that do not hold U.S. assets is the Trustee, who is in the United States.

In this context, foreign grantors usually choose Wyoming due to its modern trust statutes.

Your Private Trust Company as Trustee

For instance, Wyoming offers the possibility for grantors of a Wyoming FGT to set up a Private Family Trust Company (“PTC”) which can act as Trustee to their trust.

This PTC is typically a straightforward Wyoming LLC. As with the trust itself, such PTC can be set up anonymously under attorney-client privilege, with no public record of who is Member and Manager of the PTC.

In many instances, the First Member and Manager of the PTC is the grantor of the Trust. As a result, the grantor can retain a very high level of control over the Trust’s finances.

Further Managers (family members, trusted business partners, legal experts, etc.) can be appointed to the PTC’s board of directors to make all decisions related to the Trust.

This flexibility offered by the Wyoming PTC is in stark contrast with other jurisdictions where Trustees can only be highly regulated financial institutions staffed with remote employees rather than trusted close contacts.

Finally, a Private Trust Company can be the Trustee of more than one “related” trust. As a result, a PTC cannot solicit business with the public: its sole purpose is to act as the Trustee for a trust or related trusts.

Be your own investment advisor

From the above, it is clear that the PTC is generally used by grantors wishing to ensure their Wyoming trust is well maintained and well run and so that they can have a say in the trust’s decisions.

With this in mind, in its capacity as Trustee, a PTC can enter into agreements with any third parties such as attorneys, accountants, investment advisors, etc.

A common setup is for the grantor to be the appointed investment advisor to the PTC under such private agreement.

The net effect is that the grantor, as sole or co-beneficiary of the trust, effectively manages proprietary assets without having to step into the limelight as Ultimate Beneficial Owner, as is the case with any company setup.

In this context, it is the PTC that will open bank and brokerage accounts for the Trust and who can certify the authenticity of the Trust instrument.

In the U.S., trust instruments (including our template included with this post) often state that it is sufficient to provide partial extracts as proof of existence of the Trust, without disclosure of the Trust’s grantor(s) and beneficiaries.

Alternatively, the PTC can use its own bank account for transactions related to the Trust. It can easily get an Entity Identification Number (“E.I.N.”) and open a bank account, which can then be used as the bank account for the Trust since the Trustee acts on behalf of the Trust.

The same applies for brokerage accounts and crypto exchange accounts, which can all be held and operated by the PTC on behalf of the Trust.

In our last section, we pull all of the above together and come up with a possible structure to optimize the ownership and management of crypto assets around the world.

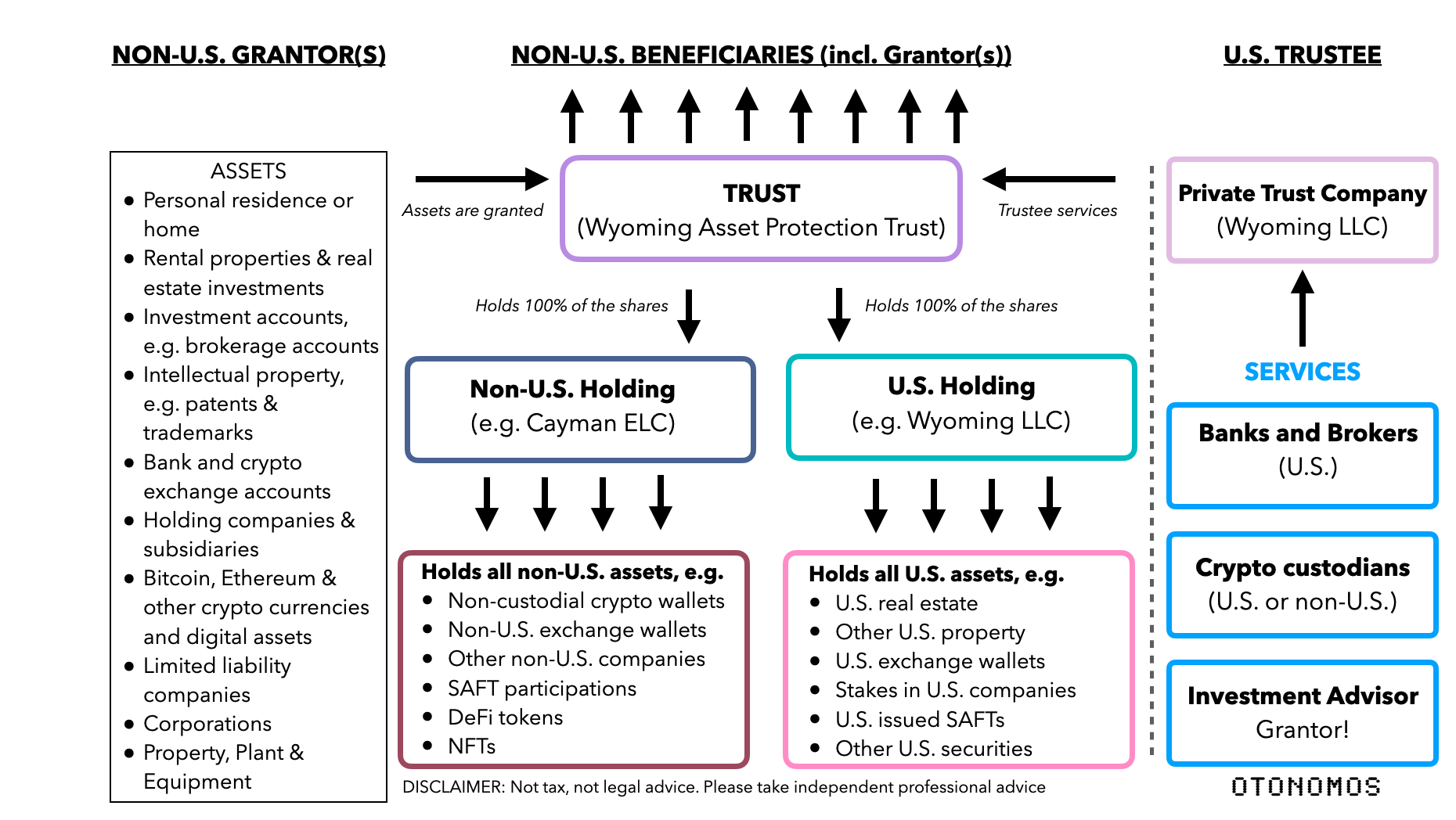

3. An optimized structure

How does the FGT hold assets?

As mentioned on the three cardinal rules above, then way for an FGT to keep assets out of the U.S. is by forming a 100% non-U.S.holding subsidiary. Such offshore holding company may in turn may hold shares in companies or other assets abroad, including crypto on foreign exchanges or self-custodied wallets in name of the holding or its non-U.S. subsidiaries.

As a result, all assets are held abroad hence U.S. income, gift, and estate taxes do not apply. Effectively, the non-U.S. holding entity together with its non-U.S. subsidiaries acts as a U.S. tax blocker.

If the non-U.S. holding entity also holds U.S. assets however, these would be subject to U.S. witholding taxes (or treaty taxes in case taxes apply where the non-U.S. entity is incorporated) at the entity level, but only if the U.S. assets produce income.

In this analysis, a U.S. Trust with foreign grantor(s) and beneficiaries could have a simple checking bank account in the U.S. and not be taxed there, since a current account generally does not produce income (and income from current accounts would be excluded anyhow).

In the same way, property - and by extension crypto assets - could be held in the U.S. in name of the non-U.S. holding as long as they do not generate income.

In relation to U.S. securities, in a grossly reduced analysis, dividends from U.S. stocks would be taxed however the proceeds of the sale of U.S. securities would not. This would generally mean that the non-U.S. holding of a FGT could have a brokerage account in the U.S. and only pay taxes on dividends. More significantly, it would imply that the FGT can take venture-type stakes in U.S. private companies, which do not pay dividends, and not be taxed on the proceeds at exit.

There is of course a lot less clarity on the treatment of shiny new digital assets. As a general rule therefore, crypto is better held in wallets belonging to the non-U.S. entity owned by the trust, since certain assets could be seen as producing revenue in the U.S., for instance DeFi governance tokens that are being staked for yield farming purposes.

However, within the logic of the tax treatment of FGTs outlined above, it would seem that crypto assets held by the non-U.S. subsidiary of a FGT off-ramped on U.S. exchanges and sent to a U.S. bank account of the non-U.S. entity would not come within the ambit of U.S. taxes. In such scenario, the U.S. is then merely the locus of where cash is parked, whether in fiat or digital form, and not where the assets that produced the cash are located.

In this context, it is helpful that U.S. banks do - in contrast with other countries - open bank accounts for non-U.S. entities, including offshore ones. As is known, some banks such as Silvergate in San Diego or Signature Bank in New York specialize in crypto clients, both U.S. and foreign.

Foreign Non-Grantor Trust (“FNGT”)

In certain instances, NRAs might find it beneficial to have the trust drafted as an irrevocable FNGT for added asset protection purposes or other home country benefits. Whether a Trust is a grantor or non-grantor trust is a question of how the Trust's income is taxed. If the income pass through to the beneficiaries, then it is a grantor trust. If the trust pays its own income taxes, then it is a non-grantor trust.

The structure and benefits are similar to the FGT discussed above and is less relevant if the grantor is an NRA. Much like the FGT, the FNGT is a popular trust for NRAs with foreign beneficiaries and property who are looking for political stability or protection of property, or to avoid the blacklisting issues of many of the offshore trust jurisdictions.

The FNGT is also best for NRAs who are not anticipating current U.S. beneficiaries.

A possible structure emerging from all this could look as follows:

- A Wyoming Asset Protection Trust settled by an NRA grantor as either an FGT or FNGT, of which the grantor(s) is/are beneficiaries under an anonymous Trust Instrument protected by attorney-client privilege.

- A Wyoming PCT of which the NRA can be Member and Manager, possibly with a Board of trusted advisors.

- Bank and brokerage accounts in the U.S. for the PCT own behalf of the Trust.

- A non-U.S. holding company to hold non-U.S. assets, including crypto assets open foreign exchanges and in wallets controlled by the non-U.S. holding. This holding is likely to also have subsidiaries or hold stakes in non-U.S. companies.

- Bank, brokerage and crypto exchange accounts for the non U.S. holding in the U.S. to offramp crypto and invest in U.S. securities if it so wishes.

- A U.S. holding LLC to compartmentalize U.S. held assets from non-U.S. assets, with one 100% subsidiary U.S. LLC through which it acts.

The types of assets that can be protected in the above setup include, but are not limited to:

- Personal residence or home

- Rental properties & real estate investments

- Investment accounts, e.g. brokerage accounts

- Intellectual property, e.g. patents & trademarks

- Bank and crypto exchange accounts

- Holding companies & subsidiaries

- Bitcoin, Ethereum & other crypto currencies and digital assets

- Limited liability companies

- Corporations

- Property, Plant & Equipment

Cost

The above setup, when instructing Otonomos, would incur the following professional fees:

- US$ 8,150 one-time fee for the setup of the Wyoming Trust + the U.S. Holding LLC in Wyoming

- US$ 5,000 one-time setup fee for the Wyoming Private Trust Company

- US$ 1,450 per annum for the registered address and registered agent to the Trust and the LLC in Wyoming

- Min. US$ 2,000 per bank account opening for PTC or Trust/LLC in U.S.

- Min. US$ 1,200 per crypto exchange account

Note: The cost of the non-US holding company depends on the chosen jurisdiction and is quoted for separately. Further trust instrument customization is at US$ 400/hour with a minimum of 5 hours.

Template trust agreement

Paying subscribers can access the 62-pages template trust agreement here: https://otonomos.docsend.com/view/rjksvkkwqqsfs3mw

(Pease note: Email authentication will be required. Use at own risk).

Book a FREE initial call to ask any questions you may have and discuss your specific needs.