Most people would agree that most people are good and that only some people are bad.

This is hopefully anecdotally true for most of us!

But it also has to be true historically. If not, the world would be fundamentally crooked and humanity would arguably not have made it thus far, since trust would have been eroded to the extent that economic exchange would have ceased to exist by now.

From this, it follows that most human activity must be within the law because most people perceive laws as roughly just. Even if they don’t, most people probably have no intent of breaking the law, either out of civic sense or fear of prosecution.

“Funny business”

As a result, we can assume that the majority of transactions resulting from economic exchange, whether in fiat or crypto, have a legitimate purpose.

Some recent research supports this: According to a recent Chainanalysis report, only 1% of all crypto transactions may be related to criminal activity.

However, despite the relatively marginal use of crypto currencies for “funny business” as the ECB’s Christine Lagarde calls it, she and other regulators seek to regulate all crypto transactions, alleging that such controls will prevent crime.

This post aims to show why, in the context of financial transactions, the crime prevention logic is creating a deanonymization dynamic that may lead to total surveillance, why this is wrong on philosophical grounds and why we should fight it with every fibre in our body.

Our right to the future tense

We are being surveilled both by private companies and by governments.

In her 2019 work on surveillance capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff provides an analytical framework that dissects the origins, motives and modus operandi of technological surveillance by private companies.

It shows how commercial surveillance provides the raw material for behavior modification tools developed by private companies and sold to the highest bidders in “behavioral predication markets”.

This profit motive, according to Zuboff, will ultimately rob us of our “right to the future tense”: instead of a future we can choose and author ourselves, our lives will be lived for us according to a “shadow text” composed by machines who harvest each and every data point about us via our phones, our computers and all the digital paraphernalia we surround ourselves with.

Fascism 2.0

There is now real debate about the use of surveillance technology by private companies.

Equally if not more disconcerting is when surveillance technology is used by governments.

It is easy to see how in the hands of authoritarian governments, the use of technological surveillance is a direct road to Fascism 2.0., in which our futures will be manipulated by political puppet masters with their hands on the algorithms and big data currently at the service of Big Tech.

Fascism 2.0 will be more subtle, less brutal, and hence less perceptible: no need to threaten people with violence or beat them into submission: simply censor their choices through behavior modification tools that will make people obey from within.

We won’t even be aware of the choices we had in the first place: our political behavior will have been programmed for us along a “second text” written by political overlords according to what they judge societally acceptable, rather than authored by ourselves as sovereign individuals.

Such soft-authoritarianism is already practiced by what are generally seen as benign and modern countries, such as Dubai and often-admired Singapore.

In the case of Singapore, though economically free, politically it is run by an elite that doesn't trust its own population.

The “tiny country jam-packed with goody two-shoes”, in the words of the late Sir David Tang, the Hong Kong tycoon, is run by zealous bureaucratic busybodies who collectively enforce a very modern version of technocratic authoritarianism.

It is the ultimate techno-paternalistic state, Huxley’s brave new world in which even moral permissiveness is manufactured and served up by a government that sets the limits of tolerance, the way kids can have half an hour of TV before bedtime.

Through a combination of carefully staged public messaging and active censorship, its citizens are being programmed to believe in their government’s foresight and benignity, whilst their privacy rights are methodically stripped away on grounds of crime prevention, public safety, and societal harmony.

Election rules are skewed to keep the same party perpetually in power, CCTV surveillance is ubiquitous without visible police presence, internet access is controlled and law enforcement is draconian. In short, government control is total.

The result is a population that seethes through its teeth in private but has been conditioned to censor its behavior, its speech and its thinking in public.

The utilitarian case

Singapore may be what the future will look like if we make intrinsic rights such as privacy and freedom of speech subordinate to a government’s narrative.

It should serve as a reminder that when we allow a degree of surveillance on narrow utilitarian grounds, we risk opening a breech in privacy as the individual bulwark against political oppression and persecution, not only by governments gone rogue, but also a self-righteous, modern state which decides for us who we can transact with, what we can say and who we can associate with.

The utilitarian argument that if we want to catch the bad guys, we need to preventatively screen all the good guys has many flaws:

- Irreducibility of crime

Perhaps we ought to accept a certain inevitability to crime, based on human nature and history (“if bad people want to do bad things, they will always find a way”). If indeed there is a certain irreducibility to crime, should we accept our freedoms to be limited in a vain effort to bring crime down to zero? - Guilty without trial

There is also a judicial objection: mass surveillance makes criminals from all of us, unless physical inspections or digital surveillance exonerate us. It is the same argument that forced toddlers to take off their shoes at airport security post 9/11: It turns the “innocent until proven” legal principle on its head and makes everybody guilty unless disproven, without anybody reading our Miranda rights to remind us that our data could be self-incriminating. Within this logic, the very use of privacy tools must mean you’re into Lagarde’s “funny business”! - Dumb pipes

In the same way social media is not liable for the user contents on its platform, should blockchains including privacy-centric ledgers such as ZCash and Monero not just be considered dumb pipes, in the same way fibre optic cable isn’t expected to filter contents passing through it? Put differently, are there better alternatives to preventing crime than wholesale surveillance of all transactions? - Ambiguity

It’s not clear how much of our privacy we are actually giving up. How come if there are rules that require a warrant to tap our phones, security and law enforcement agencies are commonly believed to monitor all our phone calls and online behavior? Where did we sign up to this? - Agency problem

There are many ways in which the classic agency problems manifests itself in this context, not only in how laws that take away our privacy on crime prevention grounds are adopted in the first place but also how officials enforce those rules in a way that the majority of people may not want.

Nowhere to hide

Many of the above points can probably be argued both ways.

However, the agency problem may be the most stubborn: If political authority is ultimately justified on the basis that it is derived from some rough political consensus amongst the ruled, then it would be a paradox if those rules go against the wishes of the ruled.

The question then becomes: how much do we actually care about privacy?

If I already agreed to private companies harvesting and storing information about me in return for free email, free internet search, free maps, always-on chat, and all the other daily comforts of modern online life, is giving up some privacy to the government not a fair price to pay if my government tells me it’ll protect me from bad stuff happening?

If I have nothing to hide, what does it harm if “they” know everything about me, if it lets “them” know everything about those who do have something to hide?

The danger with this argument is that soon, we may go from nothing to hide to nowhere to hide:

- Who can hand on their heart say that some text sent in anger, some thoughtless remark, a verbal snipe or gaudy joke posted online could not be used against them when taken out of context?

- Who can hide from an insecure government if every subversive comment or post can be seen as seditious (or if it involves Singapore’s Prime Minister, defamatory)?

- How can tax be fair if every cross-border financial transaction creates an assumption of tax avoidance?

- How can we call ourselves free if we can only send or receive money and payments from people on government-sanctioned white-lists? Who decides who’s on that list?

- How will art, poetry, creativity and authenticity thrive in the ever-presence of microphones, cameras and smart devices that capture and store our every spontaneity for perpetuity?

Decentralized delusion

The decentralization movement can perhaps best be understood as a reaction largely by technologists and technology entrepreneurs against centralized technologies that give their owners the power to censor and deplatform users.

However we think decentralists largely delude themselves if they believes that the use of blockchains protects them from censorship.

By their nature, transactions on public ledgers are traceable. Even if transactions may be unstoppable, censorship can be reintroduced by full deanonymization of all sending and receiving wallets.

Such deanonymization of private wallets would involve full attestation of one’s identity, similar to the KYC/AML checks we are required to pass whenever we want to access a regulated service.

This deanonymization dynamic is already happening in countries like Switzerland and (again) Singapore and there are proposals in that direction in the United States too.

Digital currencies issued by central banks are part of this deanonymization agenda since they are surveillable by design.

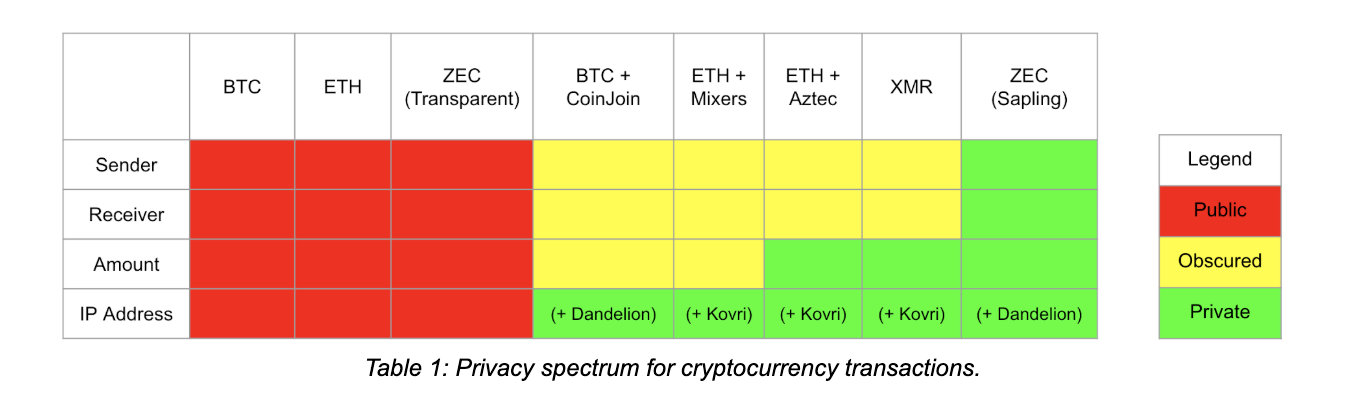

From here, it is not unimaginable that crypto currencies that are considered perfectly private (i.e. the sender, the receiver, the amount transacted, and the IP address remain successfully hidden), such as ZCash, or technologies that help offering pretty good privacy (such as “mixers”), may be banned (see Table 1 below for an overview of the privacy spectrum across BTC, ETH, MXR and ZEC, courtesy of Multicoin Capital).

Perfect or pretty good private transactions could be banned for instance by delistings from regulated exchanges, by bringing decentralized exchanges into the regulatory ambit, or by forcing private wallets to come into the open.

In such scenario, even if the contents of transactions could still be masked (how much money you send), it would be possible to link who sends and who receives to a real-world identity, similar to legacy bank accounts but with vastly superior traceability.

What this would mean is that effectively, there is no chance of being left alone: everything we do on the financial ledger will be surveilled. All our financial transactions will be inspectionable.

Freedom tools

How to escape surveillance?

Thanks to technology tools, escaping surveillance no longer means living off the grid.

ZCash makes privacy toggleable which is perhaps why for now at least regulators seem to tolerate it as a privacy coin.

The idea of privacy as some kind of user-activated blockchain VPN that shields our transactions unless we select a non-private mode has a lot of appeal.

The question still remains if there will be other ways to censor private transactions. The pendulum is firmly swinging in the direction of more controls, more checks and more regulation.

What is clear is that without privacy, there can be no censorship resistance.

Eventually, an infrastructure of ledgers and layer 2 applications will emerge that lets everybody freely participate in economic exchange with full privacy using “money without memory”.

Only then will we have global, state-free money that is both unstoppable and uncensored.